Reducing The Cascade of Interventions in Birth

Maternity care in the United States tends to be intervention-heavy. This means that when a woman is in labor, it is common for several interventions to be recommended to keep labor moving along.

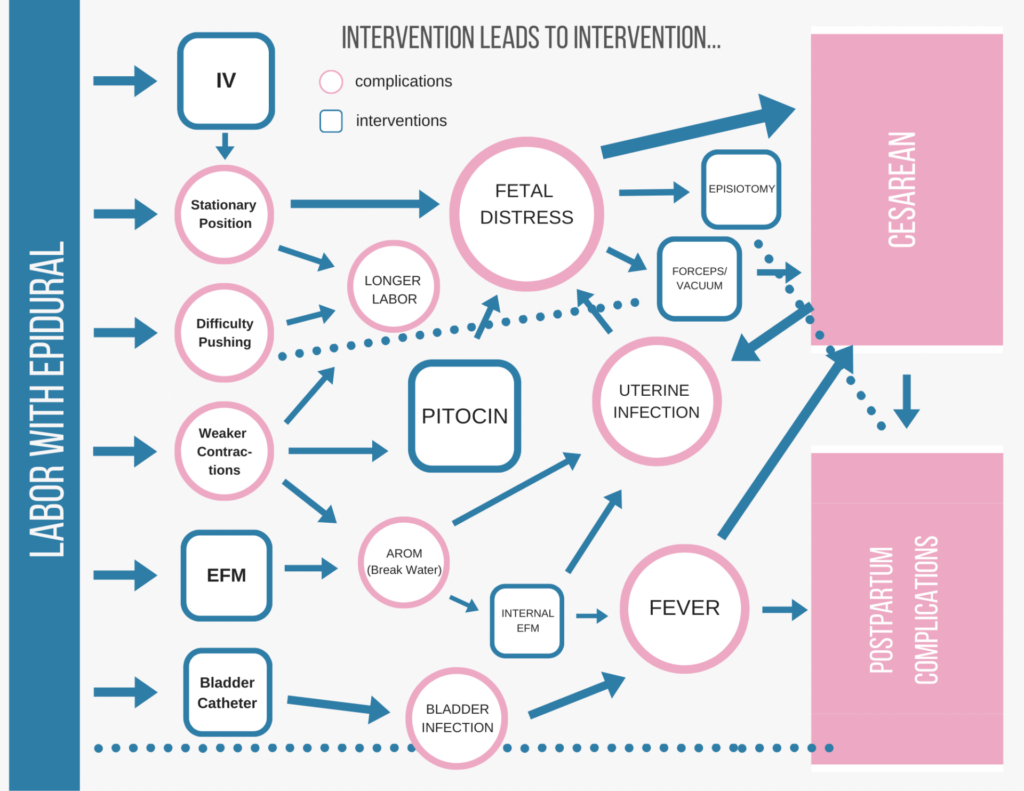

Interventions can be medical or non-medical. Some of these interventions have side effects that can lead to other medical interventions. This is sometimes called the cascade of interventions.

Why is it Best to Avoid or Minimize Interventions during Labor and Birth?

When you or your provider decide to use an intervention, the effects of the intervention may cause you or your provider to suggest another intervention. Much like taking a medication with undesirable side-effects sometimes leads to another medication to counteract the first, a series of pharmacological or technological interventions can happen because of the initial intervention.

Additionally, there is an increasing body of research that suggests that the routine use of interventions in childbirth, may actually increase complications rather than decrease the risk of trouble in labor and birth for mom and baby.

What Things are Most Likely to Lead to a Cascade of Birth Interventions?

- Labor induction

- Epidural

- Pitocin/Oxytocin use in labor

- Stationary labor in bed

- Breaking the water (also known as artificially breaking the membranes)

- Continuous electronic fetal monitoring (EFM)

Let’s Look at Each of These Common Interventions Separately:

Inducing Labor

Of all the preventable interventions leading to more interventions, induction of labor tops the list. Four out of every 10 births happen after medically induced labor. Are almost half of babies unable to trigger labor at a safe time?

The 2013 Listening to Mothers Survey found that 41% of recently delivered mothers had providers who attempted medically-induced labor. Most are induced because it was close to their due date and some because the provider was concerned about being overdue.

Labor Induction Methods

Breaking the Water

Breaking the water is one way of inducing labor, though it’s typically used in conjunction with other methods. Once the water is broken, you have to have the baby within 24 hours. There’s no pulling the IV and going home or trying again tomorrow. So if it wasn’t the right time to start labor and your body or baby are not ready, breaking your water is a ticket to many other interventions to try to get your baby out.

Pitocin

Before (or instead of) breaking the water, another induction method is typically employed. There are many ways to start and manage a medical induction, but the use of prostaglandin gel on the cervix, an infusion of fake oxytocin (Pitocin), and a drug taken internally called misoprostol are among the most common ways of starting labor.

All of these induction methods require the labor to be monitored in case the mother or baby’s body react poorly or in a surprising way. The monitoring is another intervention. Nothing else happened, there are no side effects so far, but just giving the drugs to induce requires a supplemental intervention.

Monitoring as a secondary intervention is common, and can mean electronic fetal monitoring, contraction monitoring, maternal blood pressure readings and more.

Pitocin, especially, usually leads to further intervention. Read more about this below.

Starting labor when your baby or body are not ready to be in labor has consequences. Most often these are managed well, or minimal. And some of it will come down to your beliefs about birth and what makes it safe.

Many couples who plan a natural vaginal birth and prepare to handle the intensity of labor without medications get pulled out of their planned course because of pressure to induce. An induction is almost always harder on the body and the baby, and induction very often leads to the need for pharmacological pain relief, which has its own cascade.

Epidural

An epidural requires the patient to be stationary and heavily monitored. An epidural is regional anesthesia that uses one or more pain medications. It is placed in the epidural space, right next to your spinal cord.

Here is a post dedicated to epidural benefits and drawbacks.

Nothing else beats an epidural for pain in labor, or for the subsequent interventions required to monitor what it is doing. A woman with an epidural must stay in bed, attached to six monitors.

Epidural Leads to a Guaranteed Cascade of Interventions During Birth Including:

- A blood pressure cuff on your arm

- A pulse oximeter (typically on your finger)

- A contraction monitor

- Baby’s heart rate monitor

- A urine catheter

- An IV

- And of course, the tube that goes from your spine to the iv pole

Each of these interventions has side effects of its own. In addition to essentially tying down the laboring person, any of them can be annoying or uncomfortable. Being in labor is uncomfortable enough, so having addition discomforts may be a concern, especially in the cases where the epidural fails in one or more parts of the body.

Pitocin

As discussed previously, using Pitocin (synthetic oxytocin) to induce or augment labor can have consequences that lead to further intervention. There’s no great way to predict how a body will react to Pitocin. Especially when the dose isn’t slowly ramped up, it can fatigue the uterus or distress the baby.

Pitocin makes contractions harder to handle. When your body is causing the contraction, your body provides a hormonal path to dealing with it. Forcing the uterus to contract with drugs means contractions without the hormonal benefits.

When a labor feels unmanageable because of the rate of synthetic contractions, epidurals are more often used. As we discussed, epidurals come with their own set of interventions, though some of those you would already have because of the Pitocin.

Stationary Labor in Bed

Babies need to be able to move through your pelvis to be born. They make a series of twists and turns called cardinal movements. Babies are like people: some can handle this no matter what their mother is doing, but most of us need a little help to do hard things.

Active, upright birth is easier on the mother’s body and assists the baby in coming down. One position might be good for awhile, but then the baby needs you to move.

In the case of a bed labor with epidural, the baby’s heartbeat may indicate distress and the nurse will come running into the room to flip you over. Get on one side and see if that helps the baby, try the other side. The baby is having trouble moving or is being squished. In an active birth, you’re more likely to move enough or feel enough to know how to move to keep baby moving.

If the baby indicates distress significant enough, long enough, or often enough, your medical team may encourage a cesarean delivery. If you’re unable to push effectively in your position, forceps or vacuum (or cesarean section) may be used to get the baby out.

Just remaining stationary has an effect on your labor. But no one chooses to stay in bed on their back if they don’t have an epidural or other intervention that requires this.

Electronic Fetal Monitoring

Few ‘advances’ in obstetric practice have had as big an effect as the popularization of electronic fetal monitoring. The provider can strap a sensor on your belly and it will record the baby’s heart rate, sending the tracing to the nurses’ station for the duration of labor.

This is beneficial for the nurses, who don’t have to come in as often, find the baby’s heart beat, and lean over your body while listening. And it’s appealing to doctors who can feel confident at any moment that the baby is doing fine. Unfortunately, it also makes providers skittish.

Research has established that EFM does not lead to better outcomes for mothers or babies while increasing some risks. People who have continuous fetal monitoring like this are at much higher risk for cesarean section and birth by vacuum extractor. In fact, “non-reassuring fetal heart tones” is the second most common reason for primary cesareans in the U.S. Put simply, it makes doctors nervous, especially in a highly litigious culture.

Some high-risk women may benefit from continuous EFM. Conditions that may require EFM include preeclampsia, type 1 diabetes, and Pitocin augmentation or induction.

Some interventions are less likely to cause a cascade of interventions. This doesn’t mean they are safer. For instance, using narcotics in labor is less likely to effect your labor progress, but prolonged use often causes the newborn to be born sleepy and with a depressed respiratory system.

Babies born to mothers who used narcotics throughout labor or near to pushing need a NICU team there to check on baby immediately. There is no cascade for the mother or the labor, but there may be for the baby’s first weeks.

How Can You Avoid Interventions in Childbirth That Lead to More Interventions?

1. Avoid Induction When Possible!

Most inductions are for convenience (yours or doctor’s) or for concern about being too overdue. Babies are not considered late until 42 weeks. Plan to be pregnant until 42 weeks and find a provider who doesn’t often induce before then.

2. Avoid Medications for Pain Relief as Long as Possible

Take a birth class online or with a childbirth educator, hire a doula, and learn skills to manage the intensity of labor without drugs. The longer you can wait to get an epidural or the fewer pharmaceuticals you need, the less likely there are to be consequences leading to further intervention.

3. Find the right Provider

A doctor or midwife whose philosophies about intervention use matches your own is not nice, it’s necessary. Choose a provider who doesn’t use these interventions without trying less invasive methods first. Find the provider who is right for you, take the birth profile assessment.

Disclaimer: Pregnancy by Design’s information is not a substitute for professional medical advice or treatment. Always ask your healthcare provider about any health concerns you may have.

Cited Research

Alfirevic, Z., Devane, D., & Gyte, G. M. (2006). Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) as a form of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for fetal assessment during labour. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (3), CD006066.

Childbirth Connection. The Role of Hormones.

Declercq, E. R., Sakala, C., Corry, M. P., Applebaum, S., & Herrlich, A. (2013). Listening to Mothers(SM) III Pregnancy and Birth. Retrieved from https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/health-care/maternity/listening-to-mother-iii-pregnancy-and-birth-2013.pdf

Dekker, Rebecca. (2020). Evidence on inducing labor for going past your due date.

Heelan L. (2013). Fetal monitoring: creating a culture of safety with informed choice. The Journal of perinatal education, 22(3), 156–165.

What to Eat When Pregnant

What to Eat When Pregnant

Awesome post.